Transducers.js: A JavaScript Library for Transformation of Data

If you didn't grab a few cups of coffee for my last post, you're going to want to for this one. While writing my last post about js-csp, a port of Clojure's core.async, they announced transducers which solves a key problem when working with transformation of data. The technique works particularly well with channels (exactly what js-csp uses), so I dug into it.

What I discovered is mind-blowing. So I also ported it to JavaScript, and today I'm announcing transducers.js, a library to build transformations of data and apply it to any data type you could imagine.

Woha, what did I just say? Let's take a step back for a second. If you haven't heard of transducers before, you can read about their history in Clojure's announcement. Additionally, there's an awesome post that explores these ideas in JavaScript and walks you through them from start to finish. I give a similar (but brief) walkthrough at the end of this post.

The word transduce is just a combination of transform and reduce. The reduce function is the base transformation; any other transformation can be expressed in terms of it (map, filter, etc).

var arr = [1, 2, 3, 4];

arr.reduce(function(result, x) {

result.push(x + 1);

return result;

}, []);

// -> [ 2, 3, 4, 5 ]

The function passed to reduce is a reducing function. It takes a result and an input and returns a new result. Transducers abstract this out so that you can compose transformations completely independent of the data structure. Here's the same call but with transduce:

function append(result, x) {

result.push(x);

return result;

}

transduce(map(x => x + 1), append, [], arr);

We created append to make it easier to work with arrays, and are using ES6 arrow functions (you really should too, they are easy to cross-compile). The main difference is that the push call on the array is now moved out of the transformation. In JavaScript we always couple transformation with specific data structures, and we've got to stop doing that. We can reuse transformations across all data structures, even streams.

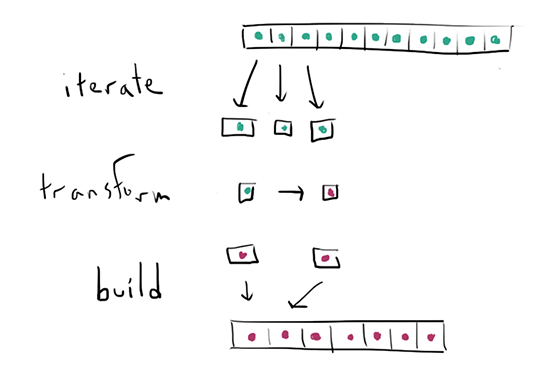

There are three main concerns here that reduce needs to work. First is to iterate over the source data structure. Second is to transform each value. Third is to build up a new result.

These are completely separate concerns, and yet most transformations in JavaScript are tightly coupled with specific data structures. Transducers decouples this and you can apply all the available transformations on any data structure.

Transformations

We have a small amount of transformations that will solve most of your needs like map, filter, dedupe, and more. Here's an example of composing transformations:

sequence(

compose(

cat,

map(x => x + 1),

dedupe(),

drop(3)

),

[[1, 2], [3, 4], [4, 5]]

)

// -> [ 5, 6 ]

The compose function combines transformations, and sequence just creates a new collection of the same type and runs the transformations. Note that nothing within the transformations assume anything about the data structure from where it comes or where it's going.

Most of the transformations that transducers.js provides can also simply take a collection, and it will immediately run the transformation over the collection and return a new collection of the same type. This lets you do simple transformations the familiar way:

map(x => x + 1, [1, 2, 3, 4]);

filter(x => x % 2 === 0, [1, 2, 3, 4])

These functions are highly optimized for the builtin types like arrays, so the above map literally just runs a while loop and applies your function over each value.

Iterating and Building

These transformations aren't useful unless you can actually apply them. We figured out the transform concern, but what about iterate and build?

First lets take a look at the available functions for applying transducers:

sequence(xform, coll)- get a collection of the same type and fill it with the results of applyingxformover each item incolltransduce(xform, f, init, coll)- reduce a collection starting with the initial valueinit, applyingxformto each value and running the reducing functionfinto(to, xform, from)- apply xform to each value in the collectionfromand append it to the collectionto

Each of these has different levels of assumptions. transduce is the lowest-level in that it iterates over coll but lets you build up the result. into assumes the result is a collection and automatically appends to it. Finally, sequence assumes you want a collection of the same type so it creates it and fills it with the results of the transformation.

Ideally our library wouldn't care about the details of iteration or building either, otherwise it kind of kills the point of generic transformations. Luckily ES6 has an iteration protocol, so we can use that for iteration.

But what about building? Unfortunately there is no protocol for that, so we need to create our own. transducers.js looks for @@append and @@empty methods on a collection for adding to it and creating new collections. (Of course, it works out of the box for native arrays and objects).

Let's drive this point home with an example. Say you wanted to use the immutable-js library. It already supports iteration, so you can automatically do this:

into([],

compose(

map(x => x * 2),

filter(x => x > 5)

),

Immutable.Vector(1, 2, 3, 4));

// -> [ 6, 8 ]

We really want to use immutable vectors all the way through, so let's augment the vector type to support "building":

Immutable.Vector.prototype['@@append'] = function(x) {

return this.push(x);

};

Immutable.Vector.prototype['@@empty'] = function(x) {

return Immutable.Vector();

};

Now we can just use sequence, and we get an immutable vector back:

sequence(compose(

map(x => x * 2),

filter(x => x > 5)

),

Immutable.Vector(1, 2, 3, 4));

// -> Immutable.Vector(6, 8)

This is experimental, so I would wait a little while before using this in production, but so far this gives a surprising amount of power for a 500-line JavaScript library.

Implications

Works with Everything (including Streams and Channels)!

Let's play around with all the kinds of data structures we can use now. A type must at least be iterable to use with into or transduce, but if it is also buildable then it can also be used with sequence or the target collection of into.

var xform = compose(map(x => x * 2),

filter(x => x > 5));

// arrays (iterable & buildable)

sequence(xform, [1, 2, 3, 4]);

// -> [ 6, 8 ]

// objects (iterable & buildable)

into([],

compose(map(kv => kv[1]), xform),

{ x: 1, y: 2, z: 3, w: 4 })

// -> [ 6, 8 ]

sequence(map(kv => [kv[0], kv[1] + 1]),

{ x: 1, y: 2, z: 3, w: 4 })

// -> { x: 2, y: 3, z: 4, w: 5 }

// generators (iterable)

function *data() {

yield 1;

yield 2;

yield 3;

yield 4;

}

into([], xform, data())

// -> [ 6, 8 ]

// Sets and Maps (iterable)

into([], xform, new Set([1, 2, 3, 3]))

// -> [ 6 ]

into({}, map(kv => [kv[0], kv[1] * 2], new Map([['x', 1], ['y', 2]])))

// -> { x: 2, y: 4 }

// or make it buildable

Map.prototype['@@append'] = Map.prototype.add;

Map.prototype['@@empty'] = function() { return new Map(); };

Set.prototype['@@append'] = Set.prototype.add;

Set.prototype['@@empty'] = function() { return new Set(); };

sequence(xform, new Set([1, 2, 3, 2]))

sequence(xform, new Map([['x', 1], ['y', 2]]));

// node lists (iterable)

into([], map(x => x.className), document.querySelectorAll('div'));

// custom types (iterable & buildable)

into([], xform, Immutable.Vector(1, 2, 3, 4));

into(MyCustomType(), xform, Immutable.Vector(1, 2, 3, 4));

// if implemented append and empty:

sequence(xform, Immutable.Vector(1, 2, 3, 4));

// channels

var ch = chan(1, xform);

go(function*() {

yield put(ch, 1);

yield put(ch, 2);

yield put(ch, 3);

yield put(ch, 4);

});

go(function*() {

while(!ch.closed) {

console.log(yield take(ch));

}

});

// output: 6 8

Now that we've decoupled the data that comes in, how it's transformed, and what comes out, we have an insane amount of power. And with a pretty simple API as well.

Did you notice that last example with channels? That's right, a js-csp channel which I introduced in my last post now can take a transducer to apply over each item that passes through the channel. This easily lets us do Rx-style (reactive) code by simple reusing all the same transformations.

A channel is basically just a stream. You can reuse all of your familiar transformations on streams. That's huge!

This is possible because transducers work differently in that instead of applying each transformation to a collection one at a time (and creating multiple intermediate collections), they take each value separately and fire them through the whole transformation pipeline. That's leads us to the next point, in which there are...

No Intermediate Allocations!

Not only do we have a super generic way of transforming data, we get good performance on large arrays. This is because transducers create no intermediate collections. If you want to apply several transformations, usually each one is performed in order, creating a new collection each time.

Transducers, however, take one item off the collection at a time and fire it through the whole transformation pipeline. So it doesn't need any intermediate collections; each value runs through the pipeline separately.

Think of it as favoring a computational burden over a memory burden. Since each value runs through the pipeline, there are several function calls per item but no allocations, instead of 1 function call per item but an allocation per transformation. For small arrays there is a small difference, but for large arrays the computation burden easily wins out over the memory burden.

To be frank, early benchmarks show that this doesn't win anything in V8 until you reach a size of around 100,000 items (after that this really wins out). So it only matters for very large arrays. It's too early to post benchmarks. (update: there are actually good perf gains even with small arrays, see here. Previously the library was doing it wrong.)

How a Transducer is Born

If you are interested in walking through how transducers generalize reduce into what you see above, read the following. Feel free to skip this part though, or read this post which also does a great job of that.

The reduce function is the base transformation; any other transformation can be expressed in terms of it (map, filter, etc), so let's start with that. Here's an example call to reduce, which is available on native JS arrays:

var arr = [1, 2, 3, 4];

arr.reduce(function(result, x) { return result + x; }, 0);

// -> 10

This sums up all numbers in arr. Pretty simple, right? Hm, let's try and implement map in terms of reduce:

function map(f, coll) {

return coll.reduce(function(result, x) {

result.push(f(x));

return result;

}, []);

}

map(function(x) { return x + 1; }, arr);

// -> [2, 3, 4, 5]

That works. But our map only works with native JS arrays. It assumes a lot of knowledge about how to reduce, how to append an item, and what kind of collection to create. Shouldn't our map only be concerned with mapping? We've got to stop coupling transformations with data; every single collection is forced to completely re-implement map, filter, take, and all the collection operations, with varying incompatible properties!

But how is that possible? Well, let's start with something simple: the mapping function that we meant to create. It's only concernced with mapping. The key is that reduce will always be at the bottom of our transformation, but there's nothing stopping us from abstracting the function we pass to reduce:

function mapper(f) {

return function(result, x) {

result.push(f(x));

return result;

}

}

That looks better. We would use this by doing arr.reduce(mapper(function(x) { return x + 1; }), []). Note that now mapper has no idea how the reduction is actually done, or how the initial value is created. Unfortunately, it still has result.push embedded so it still only works with arrays. Let's abstract that out:

function mapper(f) {

return function(combine) {

return function(result, x) {

return combine(result, f(x));

}

}

}

That looks crazy, but now we have a mapper function that is literally only concerned about mapping. It calls f with x before passing it to combine. The above function may look daunting, but it's simple to use:

function append(arr, x) {

arr.push(x);

return arr;

}

arr.reduce(mapper(function(x) { return x + 1; })(append),

[]);

// -> [ 2, 3, 4, 5 ]

We create append to make it easy to functionally append to arrays. So that's about it, now we can just make this a little easi-- hold on, doesn't combine look a little like a reducer function?

If the result of applying append to the result of mapper creates a reducer function, can't we apply that itself to mapper?

arr.reduce(

mapper(function(x) { return x * 2; })(

mapper(function(x) { return x + 1; })(append)

),

[]

);

// -> [ 3, 5, 7, 9 ]

Wow! So now we can compose these super generic transformation functions. For example, let's create a filterer. You wouldn't normally apply two maps right next to each other, but you would certainly map and filter!

function filterer(f) {

return function(combine) {

return function(result, x) {

return f(x) ? combine(result, x) : result;

}

}

}

arr.reduce(

filterer(function(x) { return x > 2; })(

mapper(function(x) { return x * 2; })(append)

),

[]

);

// -> [ 6, 8 ]

Nobody wants to write code like that though. Let's make one more function compose which makes it easy to compose these, that's right, transducers. You just wrote transducers without even knowing it.

// All this does is it transforms

// `compose(x, y, z)(val)` into x(y(z(val)))`

function compose() {

var funcs = Array.prototype.slice.call(arguments);

return function(r) {

var value = r;

for(var i=funcs.length-1; i>=0; i--) {

value = funcs[i](value);

}

return value;

}

}

arr.reduce(

compose(

filterer(function(x) { return x > 2; }),

mapper(function(x) { return x * 2; })

)(append),

[]

);

// -> [ 6, 8 ]

Now we can write really clean sequential-looking transformations! Hm, there's still that awkward syntax to pass in append. How about we make our own reduce function?

function transduce(xform, f, init, coll) {

return coll.reduce(xform(f), init);

}

transduce(

compose(

filterer(function(x) { return x > 2; }),

mapper(function(x) { return x * 2; })

),

append,

[],

arr

);

// -> [ 6, 8 ]

Voila, you have transduce. Given a transformation, a function for appending data, an initial value, and a collection, run the whole process and return the final result from whatever append is. Each of those arguments are distinct pieces of information that shouldn't care at all about the others. You could easily apply the same transformation to any data structure you can imagine, as you will see below.

This transduce is not completely correct in that it should not care how the collection reduces itself.

Final Notes

You might think that this is sort of lazy evaluation, but that's not true. If you want lazy sequences, you will still have to explicitly build a lazy sequence type that handles those semantics. This just makes transformations first-class values, but you still always have to eagerly apply them. Lazy sequences are something I think should be added to transducers.js in the future. (edit: well, this paragraph isn't exactly true, but we'll have to explain laziness more in the future)

Some of the examples my also feel similar to ES6 comprehensions, and while true comprehensions don't give you the ability to control what type is built up. You can only get a generator or an array back. They also aren't composable; you will still need to solve the problem of building up transformations that can be reused.

When you correctly separate concerns in a program, it breeds super simple APIs that allow you build up all sorts of complex programs. This is a simple 500-line JavaScript library that, in my opinion, radically changes how I interact with data, and all with just a few methods.

transducers.js is still early work and it will be improved a lot. Let me know if you find any bugs (or if it blows your mind).

JAMES LONG

JAMES LONG